El Paso Sector Migrant Death Database

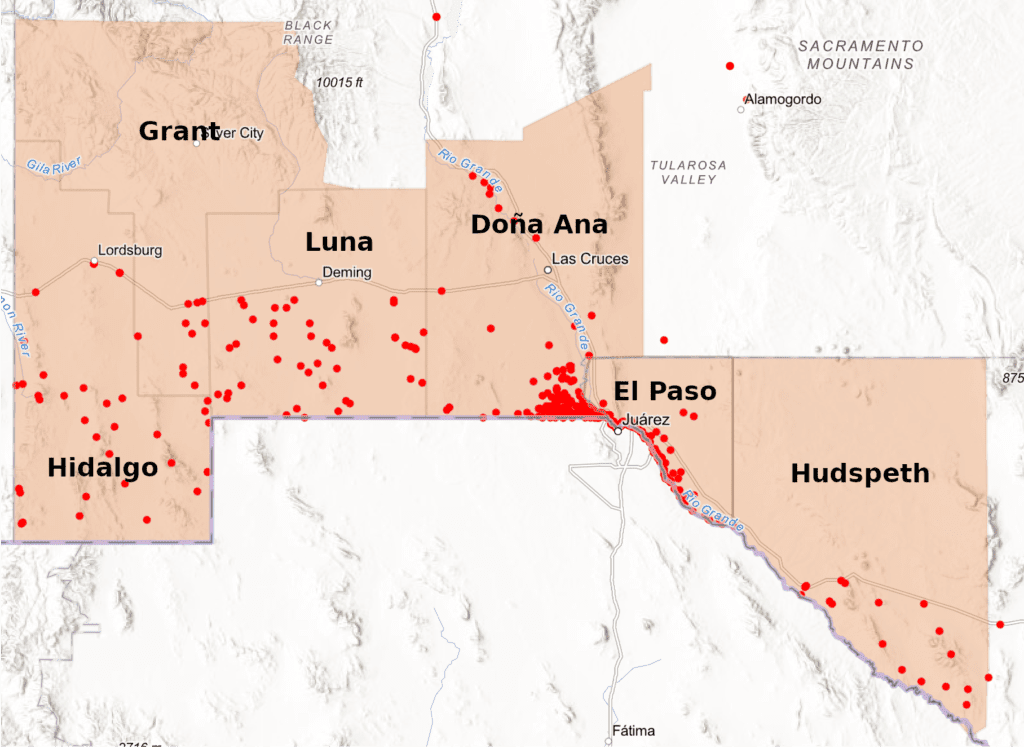

CBP’s El Paso Sector consists of El Paso and Hudspeth Counties in Texas and the entire state of New Mexico. The sector shares 264 miles of border with Mexico, of which 179.5 miles are in New Mexico, compared to 372.5 miles in Arizona, 140.4 miles in California, and 1241 miles in Texas. The six main border counties included in this study (Doña Ana, Luna, Grant, Hidalgo, El Paso, and Hudspeth) are all situated within the Chihuahuan Desert, a high desert with areas of relatively flat sandy or rocky terrain punctuated with occasional mountains, and then, in the western Bootheel of Hidalgo County, a rugged mountain landscape.

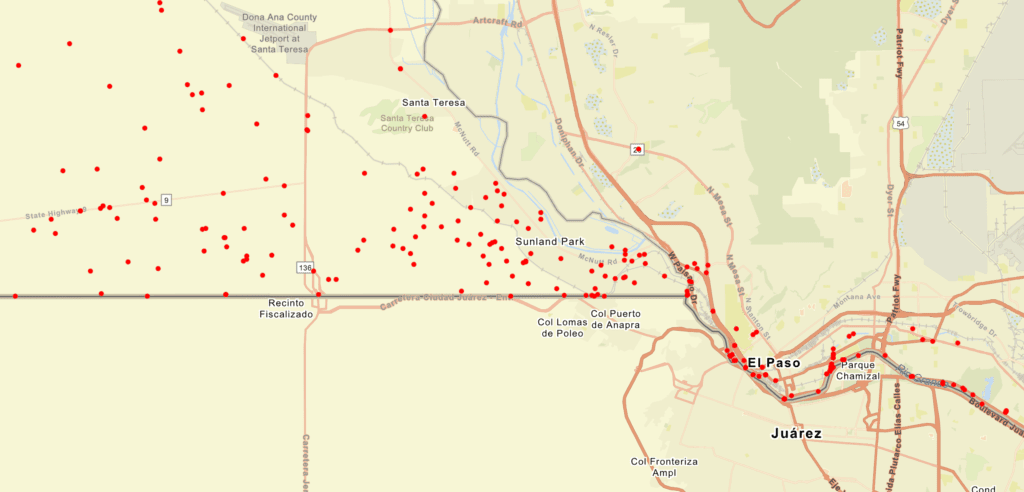

The overwhelming majority of remains discovered in the El Paso Sector have been close to the border in El Paso, TX, or just west of the city along the major migration routes in Doña Ana County, through and between the densely populated suburbs of Santa Teresa and Sunland Park. Neighborhoods and highways here are separated by stretches of open desert. I-10 runs north from El Paso along the Texas-New Mexico border to Las Cruces, and railroad tracks run northwest from El Paso through remote desert to meet with I-10 further to the west.

Pedestrian border barriers line almost the entirety of the El Paso Sector, with the exception of areas in the bootheel.

Methodology

Data Sources

El Paso Sector migrant death data was obtained through public records requests made to the University of New Mexico’s Office of the Medical Investigator (NMOMI), which is the medical investigator’s office for the entire state of New Mexico; to the El Paso County Office of the Medical Examiner (EPCOME); and to the Justices of the Peace for Precincts 1 and 2 of Hudspeth County. Additional data for this database was collected from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Missing Migrant Project database, news reports, CBP press releases, statements from the Sunland Park Fire Department, and the New Mexico Department of Transportation (NMDOT).

We used border-wide data from CBP and Arizona data from the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner (PCOME) to compare migrant mortality over time across different sections of the U.S. border.

Defining and Identifying Migrant/UBC Deaths

We have chosen to use the terms Unauthorized Border Crosser (UBC) and “migrant” interchangeably. To identify migrant/UBC deaths, we adapted the best practices from the University of Arizona Binational Migration Institute’s Protocol Development for the Standardization of Identification and Examination of UBC Bodies Along the U.S.-Mexico Border, and “Symposium on Border Crossing Deaths: Introduction” by Bruce Anderson and Bruce Parks (2008). We define a migrant/UBC death as that of a person who died in the process of furthering their entrance into the United States from Mexico between ports of entry, regardless of their intention to migrate. We also include cases in which a person crossing the border died after a hospital stay, of any length, or died in custody a short time after being apprehended.

While we did not have access to the full range of investigative resources and other data at the disposal of the NMOMI, autopsy reports generally provided enough information to make a positive UBC identification. For example:

This 27-year-old woman, [redacted], died of a snake bite with hyperthermia due to environmental heat exposure as a significant contributing factor. The manner of death is accident. According to reports, [she] was traveling with a group of people near the US border when she was bitten by a snake. Border Patrol officials were called and given the coordinates of where she was located, and the group left her there. When the agents arrived to the location, [she] was found in distress. She was speaking with medical personnel when she became unresponsive, [text redacted in original document].

In this instance, the person was actually found many miles north of the border; often phrases such as “near the US-Mexico border” are coded to imply the person is a UBC case rather than indicate their true location at time of death. Sometimes there are explicit references to a person crossing the border, evading Border Patrol, or falling from the border wall. We flagged other cases of unidentified skeletal remains found in common crossing areas as UBCs unless something specific indicated otherwise.

Some vehicle-related incidents were difficult to classify; in a region where there are many residents without US citizenship, nationality information in the death data does not shed light on whether a person was a migrant. Information gathered from news articles, social media posts, and CBP press releases, as well as NMDOT, was used to clarify some of these cases; others remain unconfirmed.

Location Data

Location data in NMOMI and EPCOME reports consisted of GPS coordinates and descriptive locations. When both existed we verified that the data matched, and where there were no GPS coordinates, we used milemarkers, addresses, and other physical location descriptions to create coordinates. We labeled these according to their level of accuracy (.25 miles, <1 mile, etc). Where there was no location data, where the description was very vague, or where only the county was available, we placed the coordinates at our best guess and labeled the accuracy as the approximate size of the county.

Volunteers also made trips to the field to verify locations of physical descriptions, signs/markers not available on any known internet database, and confusing or contradictory locations.

Independently Reported Deaths

Death data from sources other than the NMOMI and EPCOME (e.g. IOM, CBP press releases, news reports) were tracked in a separate database and then cross-referenced to match cases through date, location, and personal information. We added any unmatched cases to the database using the date in place of a case number, or kept the existing IOM case number.

Types of Incidents

We organized deaths into eight categories: vehicle-related, train-related, skeletal (where cause of death is undetermined), water-related, environmental exposure (any death that was result of being outside without adequate shelter or supplies; dehydration, heat stroke, heat exposure, cold exposure, and other medical conditions or injuries that would not otherwise have been fatal, or were caused by exposure), unknown (cases for which the medical investigator was unable to determine cause of death, or instances where an autopsy report was unavailable), homicide, wall fall, and other.

Post-Mortem Interval

Our data sources did not include a post-mortem interval (PMI) in the provided reports. As rates of decomposition vary greatly in harsh conditions, we opted to state the level of decomposition (mild, moderate, advanced, mummified, skeletal) rather than provide an estimate of PMI. In some cases, we estimated a PMI of one or two days if clearly supported by the evidence, such as a statement indicating that the person had died the previous day.

Border Enforcement Deaths

We included a separate flag for deaths caused by falls from the border barrier, pursuit by law enforcement, use of force by law enforcement, while in the custody of law enforcement, or while law enforcement was responding to medical distress. Wall fall deaths include fatal falls off of the border wall on the US side, and border enforcement deaths include fatal accidents resulting from Border Patrol chases, with the majority of these occurring in motor vehicles, but also on foot. In-custody deaths include deaths occurring after arrest and in Border Patrol custody, or within a week of incarceration due to injuries sustained while crossing the border and not properly treated. In-custody deaths do not include any deaths occurring during an attempted rescue.

These categories mirror imprecisely those that CBP’s Office of Professional responsibility (OPR) use to track and report CBP-related deaths.

There were often clues in autopsy reports suggesting that a person may have been injured or killed by a fall from the wall, or by a Border Patrol chase, but we only included these cases when the autopsy or investigator’s report clearly showed that they were a result of falls from the border wall or a law enforcement chase. Separate flags for “Possible Chase” and “Possible Wall Fall” track these uncertain cases, but they are not included in counts of border enforcement deaths.

There is also a flag for “BP Inaction,” which includes deaths in which Border Patrol failed to quickly initiate a search for a person in distress, or prevented other agencies or groups from searching for a person in distress (these are common Border Patrol practices, extensively documented in a previous report by No More Deaths). Due to the subjectivity of this flag, we have not included these cases in the count of border enforcement deaths.

This database differs from similar accounts of CBP-related deaths in that we include deaths caused by other law enforcement agencies, and we exclude any CBP-related deaths of non-migrants.

Dataset Limitations

This dataset, though more comprehensive than any other for CBP’s El Paso Sector, can be assumed to undercount or misrepresent the sector’s migrant deaths due to various limitations.

Between 2011 and 2023 we found 9 independent reports of migrant deaths not reflected in data obtained from a medical examiner’s office. So far, we have no good guesses as to why these cases would not be present in medical examiner data, but this suggests other deaths are likely not reflected in the database.

GPS coordinates were provided by the NMOMI for only two thirds of recorded cases, and, after fixing data errors, at least 18% of those coordinates turned out to be incorrect, or did not match the recorded physical description, with some coordinates placed hundreds or even thousands of miles from the actual location. The EPCOME provided GPS coordinates for less than 25% of cases, and Hudspeth County provided coordinates for over 75% of cases.

Physical descriptions and clues from the autopsy report often provided reasonably accurate locations, but sometimes they were vague or even led to nonexistent locations. NMDOT requests clarified some sites, and volunteers ground truthed others, but some locations proved too vague to mark with any confidence, and we were sometimes left only with data at the county level. Almost 25% of deaths in this dataset are presented with limited location data or locations less accurate than .5 miles.

In addition to the above difficulties, the true death toll of people migrating through New Mexico will never be known because many remains are never found. Decomposition can take place very rapidly in desert conditions, and remains can be hidden from view or scattered. Heavily decomposed and skeletal remains are discovered even in densely populated areas, so we can only imagine how many remains are never found in the more remote areas of the Chihuahuan Desert, where so many migrants cross.

We are also missing death data for the Mexican side of the border, where migrants face at times equally perilous conditions before they begin the US portion of their journey. For example, we have data for people who died falling north off the wall into the United States, but no data for those who died while falling south into Mexico.

Border Patrol Accountability

CBP Data and Undercount

Researchers and journalists have extensively shown how CBP’s migrant death data—cited by scholars, journalists, and those who make the policies that most affect migrant mortality in the borderlands—is an undercount of the true number of recovered migrant remains (itself an undercount of the unknowable number of people who have disappeared crossing the border). An AZCentral article comparing BP data for each of the US states bordering Mexico “found anywhere from 25 percent to nearly 300 percent more migrant deaths over five years,” compared with CBP’s numbers. CNN found “at least 564 deaths of people crossing illegally in the border region” in excess of the official CBP count between fiscal years 2001 and 2017, including one death in the El Paso Sector in a year when that sector had recorded no migrant deaths.

The Intercept cites a 2021 report by the Binational Migration Institute showing that Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector reported 488 migrant deaths from 2014 to 2020, while officials with the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner counted 855 for that same area. From 2012 to 2016, AZCentral found four times the amount of deaths in the El Paso Sector than reported by CBP.

A 2022 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) complaint recently put this issue in the spotlight, but CBP has failed to more accurately count migrant deaths using data available from medical examiners or other sources.

Because we have only obtained two years of data for Hudspeth County, we can’t fully quantify CBP’s undercount, but from 2012 to 2022, our database shows a higher number of deaths than CBP’s data for the El Paso Sector, with some years showing as much as two, three, or even four times (in 2020) as many deaths.

By making our database public we hope to make it easier for CBP to improve their official count, and for independent researchers, journalists, and humanitarian aid groups to find this information easily, quickly, and without having to collect and verify the disparate elements that form this database.

In addition to issues in the reporting of migrant mortality statistics in general, this database also reveals serious shortfalls in CBP’s reporting of deaths caused by border enforcement.

Border Enforcement

Medical examiners often attribute deaths directly to law enforcement or CBP. We’ve flagged these cases, which include chases on foot or in a vehicle, falls from a border barrier, use of force, and deaths in custody. We also flagged cases in which a person died after being found in medical distress by BP.

We consider border enforcement to be the cause of virtually every migrant death on the border, but cases are only included in our count if there is a direct reference in the report to one of the above circumstances. We flagged cases in which the autopsy or investigator report describes Border Patrol’s failure to launch a search for a person in distress, and though this could have contributed to a death we chose not to include these, as there is no way to know what would have happened had a proper and timely search been conducted. Deaths in areas where migrants are dropped off to avoid a BP checkpoint are certainly a direct result of enforcement, but these were also not included.

Because medical examiner reports provide inconsistent kinds of detail about the circumstances around deaths, the numbers we’ve tracked are likely an undercount. Even so, we can directly attribute 15% of all migrant deaths in CBP’s El Paso Sector to wall falls, chases, use of force, and custody. This does not include the numerous cases we found of non-migrants killed by Border Patrol.

OPR currently tracks CBP-related deaths, including deaths in custody, arrest-related deaths, use of force incidents, falls from a border barrier, deaths that occurred after someone was found in medical distress, deaths caused by pursuit or being struck by a vehicle while in pursuit. As part of this reporting process there is an obligation to release relevant deaths on CBP.gov.

While this is a step forward, falls from the wall are only “reportable” if CBP was present at the time of death, and the number of pursuit deaths is suspicious at best. For the fiscal year of 2021, for example, CBP reports 17 wall deaths, 8 of which are from the San Diego Sector. Our database shows 9 wall deaths for that calendar year. CBP documented 8 pursuit deaths border-wide, while our database contains 4 for that calendar year. It is hard to believe that half of all pursuit and wall fall deaths were in the El Paso Sector in a year when that sector accounted for less than 7% of migrant deaths border-wide.

Of the 16 CBP-related deaths we’ve identified for 2022, only 6 appear in the official OPR account obtained by FOIA requests. This suggests an alarming shortfall in OPR’s accounting of these deaths and underscores the need for oversight, data collection, and accountability by entities independent of border enforcement agencies.

A recent report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found that, in 2021, Border Patrol for the first time accounted for the highest number of arrest-related deaths among federal law enforcement agencies. This report used CBP’s own data, which we assert is a serious undercount. Among all federal agencies surveyed “[a]n immigration violation was the most serious offense allegedly committed by decedents in 46% of arrest-related deaths in FY 2021.”

Similar flags have not been made by Humane Borders or in other databases of migrant deaths, so it isn’t possible to compare this data to other CBP sectors. Aside from 2022, CBP’s incomplete data can’t be used for this comparison either because it is not disaggregated by state or even by sector.

Obtaining similar data for other states or sectors would be an important step towards Border Patrol accountability and understanding the varying effects of border enforcement on different areas of the border.

Wall Falls

Mr. [redacted] appeared to have fallen from the very high border wall at the US-Mexico border. He sustained very serious injuries, but they were not necessarily instantly lethal. The scene findings suggested he survived the fall initially but was left behind, which is likely due to his inability to walk far with his injuries. The high temperatures in the region the days around his being found were well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit; and he did not appear to have food or water with him. The presence of decomposition makes it more difficult to test for dehydration, but the scene is compelling for Mr. [redacted] sustaining serious injuries in a fall and then being left out in the elements where hyperthermia would have likely contributed to his ultimate death.

– Luna County autopsy report 2019

Pedestrian border barriers, almost all constructed during the Trump administration, cover most of El Paso Sector’s 264 miles of US-Mexico border. Rather than reduce the number of attempted crossings, this sector has seen a dramatic rise in migrant apprehensions, in addition to an ecological disaster that has been well-documented elsewhere.

A drive along this wall in Doña Ana County will reveal countless makeshift ladders dangling from the top. It’s tempting to laugh at the apparent ineffectiveness of this expensive project, but a grim picture emerges from our database, which finds at least 26 deaths attributed to falls from the border barrier in CBP’s El Paso Sector since its construction.

Most of the wall deaths we record here were not publicly reported by any entity, official or independent, which makes reading these reports all the more striking. Our numbers only begin to tell the story of the damage caused by disability or injury as a result of nonfatal falls from the wall. Sunland Park Fire Department has reported responding to five severe injuries from wall falls in a single day. Texas Monthly, after obtaining some of this data, reported on some of these injuries in October 2023:

Almost as soon as construction got underway on the taller fence, University Medical Center began seeing an uptick in these injuries. Since 2019, the trauma center has treated about 1,100 patients who fell from the top, or near the top, of the barrier. (The two other level 1 trauma centers located on the Texas border, both in the Rio Grande Valley, did not respond to requests for their data on injuries associated with the border wall.) The U.S. Border Patrol would not provide to Texas Monthly the total number of wall injuries it has tracked in recent years, or comment on how much those figures have changed since the taller fence was built.

In two separate 2022 cases in El Paso, BP found migrants in medical distress due to a fall from the border barrier, only to attribute their death to something else. One of these migrants, a young woman from Honduras, passed away en route to the hospital, but CBP does not attribute her death to a wall fall, and though the medical investigator finds the cause of death to be “blunt trauma,” the report never once mentions the border wall. Only the Honduran news reported the death as a wall fall. In the other case, an El Salvadoran man was found near the border barrier, where he had badly injured his back in a fall, and died on the way to the hospital. His cause of death was listed as “environmental exposure.” The omission of the basic facts of these cases by the EPCOME and CBP suggests an attempt to deflate the numbers of these deaths.

In El Paso there is an added difficulty in counting wall fall deaths because of the border wall’s proximity to the city’s canals. Migrants can fall off the wall almost directly into the canal, so that some drowning deaths may actually be the result of a fall from the border barrier. We have tracked multiple drowning deaths where the decedent had fallen directly from the wall into the canal and drowned, or drowned after being injured from a fall. By CBP’s own definition these deaths should be considered wall fall deaths.

Wall falls have been better-studied in California, where hospitals have been dealing with a large increase in injuries due to falls from the heightened border wall. In Arizona, with many more apprehensions and deaths than New Mexico, the number of deaths from falls is somewhere around eight since 1998 (rough estimate from Humane Borders map), whereas in the El Paso Sector there have been at least 28 deaths from falls in just the five years after new construction in 2017.

Many injuries are not reported, and Border Patrol has been known to deport people without giving them medical treatment: one volunteer at a migrant shelter in Palomas, CH, told us about sheltering a young man who had been deported with two broken legs. He had received no medical care while in custody, and became permanently disfigured as a result. Injuries and mortalities also occur on the Mexican side, and we currently do not have access to any of that data.

Pursuit

Border Patrol chases make up half (35 of 73) of the border enforcement deaths that we’ve tracked, 20 by vehicle and 15 on foot. These chases are an unnecessary and dangerous practice.

Border Patrol often chases anyone trying to evade an immigration checkpoint, or any car they find suspicious, at times employing Vehicle Immobilization Devices (VIDs) such as road spikes to stop those fleeing. A 2019 LATimes report tracked 500 cases of BP vehicle pursuits between 2015 and 2018 and found that Border Patrol’s loose policies on when to initiate a chase and the strategies used in those chases meant that “1 in 3 ended in a crash,” counting at least 250 injuries and 22 deaths.

In addition to car chases, Border Patrol also regularly chases people traveling on foot through the desert, often at night and in very rugged terrain. This dangerous practice, as well as the Border Patrol practice of “buzzing” groups by helicopter (flying a helicopter very low over a group traveling on foot, kicking up dust and generally intimidating and disorienting groups) can lead to injuries, cause groups to split up, lose their way, become more dehydrated or disoriented, drop their water or food, and greatly increases their chances of death.

In El Paso, these foot chases often result in migrants falling or jumping into the city’s deadly canal system, or crossing a busy highway.

CBP is known to engage in intentional cover-ups of many of these cases. We have found multiple references in the data showing that investigators were unable to interview BP agents involved, or that a full investigation was made impossible. After a chase in 2017, resulting in the deaths of one migrant and one US citizen, NMOMI’s investigator report states:

“Multiple attempts were made to acquire additional scene information; however, this information was unable to be obtained at the time of this autopsy report… The information given to OMI from CBP was vague and was not [forthcoming] in regards to the circumstances of the High pursuit chase.”

During a 2018 foot chase, an OMI Field Deputy (“FD”) wrote that Border Patrol tracked the individual until he died, then brought the decedent out to the road in a pickup truck, and while there was no immediate evidence of trauma, “FD never gets to see scene, FD never gets to interview brother, only sees dec in back of PU in rain storm.”

We think it is likely that many other deaths, whether or not we were able to identify them as caused by a chase, may have been given a similar treatment.

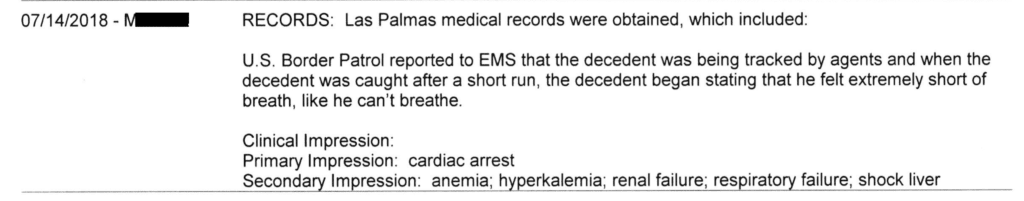

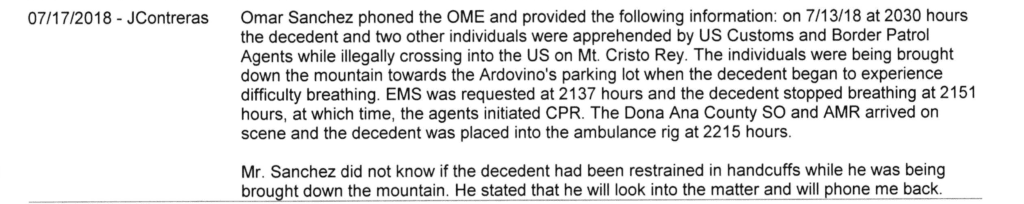

In El Paso it becomes more difficult to track these cases, as most pursuits are on foot very close to the border wall. Investigator reports and interviews with BP agents involved often use such passive language that it’s at times difficult to ascertain whether an individual was being chased or whether they were only being observed or “tracked” by BP.

As with wall falls, there is currently no measure of the nonfatal consequences of chases. Data acquired from NMDOT for the 2021 chase described above reveals more unsettling detail. In addition to the woman who was killed in the incident, nine additional passengers inside the vehicle were “severely injured,” including a 9-year-old child from Mexico. One of these passengers later died in the hospital in El Paso. A fuller account of the suffering caused by US border policy must include these kinds of injuries.

Custody

In-custody deaths were flagged, not including those deaths in which the decedent was receiving emergency medical services or in which law enforcement was responding to a distress call.

These include an 8-year-old child who passed away on Christmas in 2018 after failing to receive adequate medical treatment, and a man who was arrested with a bullet in his head and died while incarcerated 3 days later. A Brazilian man who fell ill in the desert, likely with heat stroke, was arrested and, receiving no medical attention, passed away twenty minutes later in the BP vehicle. Field investigators were not allowed to interview the BP agents involved.

In a 2021 case, which was never reported by CBP, Van Horn Watch Commander Marc Chavez told the medical investigator “The decedent was never in Border Patrol custody; however, the decedent was being detained.” This agent seems to be trying to avoid the necessity of reporting the death as in-custody, maybe not knowing that by the standards of the Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) of 2013 (PL 113-242) adopted by CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility, there is no difference between the death of someone in custody or merely “detained.”

Other Enforcement-Related Deaths

The “use of force” category uses the OPR definition:

Death was the direct result of a use of force by CBP personnel. This category would include shooting incidents, Collapsible Straight Baton strikes, Electronic Control Weapon deployment, Offensive Driving Techniques, Vehicle Immobilization Device (VIDs), or other applications of force.

Including offensive driving techniques is difficult, as these details were almost never included in reports, but we were able to find one case in which a VID was implemented, and another where BP “rammed” a car that then lost control.

Cases were flagged as “BP Inaction” if there was evidence that BP failed to respond to a distress call. These cases are not included in any of our counts of Border Enforcement deaths.

“Medical distress” cases are those in which BP found someone in medical distress and the person passed away either while being treated by emergency medical services or being brought to medical treatment by BP. These are tracked (albeit poorly) by CBP as CBP-related deaths.

Deadly Asylum Policy

The decedent and NOK [next of kin] went to the US Border to ask for asylum a few days ago; however, they were denied. The decedent and NOK contacted men to assist them to cross over from the Mexico Border to the US. The following information was provided by Sgt. Balknap #1020 and confirmed by NOK. The decedent and NOK have a son in Tennessee.

2021 El Paso County Office of the Medical Examiner investigator report for 46-year-old Cuban man

Three men assisted the decedent and NOK to cross the Border Wall from Mexico to the US. A ladder was placed on the Mexico side and a homemade rope harness was placed on NOK around her pelvis area. NOK climbed the ladder first and when on the US side the three men assisted her down with the rope harness. Prior to the decedent getting on the ladder he stated to be afraid of heights. The decedent’s harness was placed around his chest. The decedent climbed the ladder and when at the very top the decedent stated “l’m afraid, I’m afraid”. The decedent was viewed to fall from the top of the 30 ft wall. Nobody pushed the decedent. NOK relayed it all happened so fast she was not sure if the harness snapped off the decedent. The three men left when the decedent fell.

In the summer of 2021, a 49-year-old Brazilian woman, Lenilda Dos Santos, was found dead in a rural area of Luna County, New Mexico. She had initially attempted applying for asylum between ports of entry near the city of Mexicali, only to be deported back to Brazil after a stay in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facility. After she was deported, Lenilda immediately returned to try crossing through the desert west of El Paso. She shared coordinates of her location with her family until she ultimately died in a field. Even with exact coordinates, and even though Border Patrol was tracking her through the desert until the group she was with became separated, it took authorities over one week and multiple searches at the insistence of her family to find her body, which by that point was unidentifiable.

Recent human remains recovered in the El Paso Sector have more closely resembled the demographics of those seeking asylum, both by nationality and gender. In 2023, women made up over 50% of recovered human remains in that sector, a ratio with no precedent in any year for any sector where this data is available. Though data on nationality is severely lacking, what little information we do have shows a higher number of deaths of non-Mexican migrants as compared with other sectors.

Hiking through the desert to reach the United States has generally been a form of border-crossing reserved for younger men, with Mexican men historically representing the majority of known deaths in the Arizona desert. We believe these higher numbers of female deaths are connected to recent and continuing restrictions on asylum, and closures of ports of entry to asylum seekers.

In 2017, the Trump administration began an illegal metering policy at ports of entry, in which asylum seekers were blocked from presenting themselves after a daily limit had been reached. This was followed in 2019 by the Migrant Protection Protocols, and then in 2020 by Title 42. These measures prevented people from applying for asylum at ports of entry and forced them to wait indefinitely in dangerous conditions in Mexican border communities. Many of those seeking asylum were thus pushed into desert crossing routes they were often not prepared for. Though these specific policies have mostly been rolled back, many of the same policies have continued informally or under different names under the Biden administration, including the illegal practices of metering and turnbacks, in which asylum seekers are turned back from ports of entry unless they have an appointment which they can only make using the CBPOne app, as well as a return to Title 8, which further criminalizes migration and heightens the consequences of being apprehended by Border Patrol.

Unable to present themselves for asylum at ports of entry, or stuck in limbo for long periods of time waiting for an appointment with CBPOne, many people have begun crossing the border in between ports of entry to present for asylum once apprehended by Border Patrol on US soil.

Volunteers interviewed migrants waiting for CBPOne appointments in shelters in Anapra, a suburb of Juárez just south of Sunland Park. With wait times of a year or even longer, many said they are tired of waiting and considered taking their chances with a desert crossing, or by trekking over Mt. Cristo Rey.

Further restrictions on asylum, like Texas Senate Bill 4, or those proposed by the White House and US senators for 2024, will only worsen the toll of death, injury, and suffering on the US-Mexico border, as people escaping violence, poverty, and climate change are forced to find alternative ways to enter the United States.

An Urban Graveyard

We were specifically there to investigate a death site by the train tracks, then drove to the cemetery. We passed that area twice. The body was in the town near the traffic, horrifying because it was just feet from the road. It was like 105 that day. We saw eight or nine dead cows while driving towards Sunland Park.

From the place he died you could see the cemetery parking lot right there across the road, you could even see some gravestones from that spot. There were cars in and out of the parking lot in that area, just adding to the craziness that nobody else saw it, or that they didn’t report it if they did see it.

I don’t know why nobody saw it, maybe people weren’t paying attention. Seemed like there were a few people an hour visiting the cemetery. It was just pretty horrifying, right outside of people’s homes.

-Eric, desert aid volunteer, July 2023

Prevention Through Deterrence

Finding a migrant dead by a busy road while researching migrant deaths underscores the importance of publishing this data, but also makes painfully literal the image—often invoked by those writing about death in the borderlands—of an open graveyard. In El Paso and its New Mexico suburbs of Sunland Park and Santa Teresa, it has become commonplace for bodies to turn up just a short walk from help.

The US Border Patrol’s modern border enforcement strategy, Prevention Through Deterrence, was launched in 1994 with the stated goal of making migration more deadly by increasing border enforcement in urban areas and forcing migrants to cross through “more hostile terrain.” Official estimates by CBP put the migrant death toll somewhere around 10,000 since the enactment of this policy, but the true number is far higher, as data collection and reporting is flawed and the remoteness of the locations of these deaths mean that many, if not most, remains are never found or recovered.

This strategy was inspired by the “success” of El Paso’s Operation Hold the Line in 1993, in which 400 Border Patrol agents lined up within 100 yards of each other on the urban border of El Paso and Juárez to try to prevent all urban crossings. Attempted crossings went down in the short term, but today, the El Paso Sector once again makes up a large share of migrant apprehensions and deaths after other sectors have increased enforcement. Greg Abbot’s much-criticized Operation Lone Star has increased Texas’ border enforcement budget by $3 billion since March 2021 to hire more enforcement personnel, build border barriers, install more razor wire and marine barriers in the Rio Grande (as well as razor wire between New Mexico and Texas), and push more people back to areas such as El Paso.

BP’s ever-increasing yearly budget is 10 times larger than it was in 1993, with a newly built border wall and ever-more high-tech surveillance systems, towers, drones, sophisticated sensors, and laws and policies that criminalize people from helping migrants in distress. Increased outsourcing of this border enforcement strategy to other countries has caused the journey to the border to become longer, more dangerous, and more expensive, and practices such as lateral deportations and the increasing criminalization of migrants have made the consequences of getting caught much more serious, while a segregated and ineffective emergency response system has left many of those migrants who do call 911 stranded, often dying while they await a rescue that never comes.

Migrant death data, as well as Border Patrol’s migrant apprehension data, are both highly flawed datasets for a number of reasons. As previously discussed, migrant deaths are highly undercounted and do not account for all those whose remains are never recovered. Title 42, and now the Biden administration’s restriction of regular asylum processes, have inflated CBP reports of migrant apprehensions. Keeping this unreliability in mind, our data shows a comparable “migrant death rate” (of deaths divided by apprehensions) in CBP’s El Paso sector, where the bulk of remains are recovered in a populated area, and Arizona, where remains are generally recovered far from population centers.

In addition to location data which shows the difference in concentration of migrant deaths in NM and AZ, levels of decomposition tell a similar story, with skeletal remains making up over 50% of recovered human remains in Arizona and only 10% in our database.

A map of death sites by gender shows a relative lack of female recovered remains in rural Hidalgo County and other more remote areas, and high concentrations in Doña Ana and El Paso counties and close to roads. One possible explanation is that these are considered to be easier places to cross into the United States. Interviews with migrants crossing the border in the Sunland Park/Anapra area have revealed a perception of the area as safer than notoriously deadly areas such as Arizona and the Rio Grande Valley in Texas; the terrain is relatively flat, and in Doña Ana county there is adequate cell phone reception, as well as clearly visible roads and populated areas within a short hike.

The unforgiving heat of the Chihuahuan Desert can be deadly. And climate change means that recent summers have been increasingly harsh. But weather has not caused the significant increase in the numbers of people dying while crossing the border. Recent analysis by University of Arizona researchers shows how the increased level of exertion required by migrants crossing the border on foot is a better predictor of mortality than ambient temperature, and location data for El Paso sector deaths show how increasingly people are dying close to help. Narratives implying that the desert has become inherently more deadly are flawed and ignore the primary factor in death and disappearance in the borderlands: a militarized border zone in which a whole category of people is treated as less than human, forced to travel clandestinely and unable to access basic emergency services.

In 1993, cities were a relatively safe place to cross into the United States, but death data for the El Paso Sector underscores how, in the 30 years since Operation Hold the Line, the border has become militarized to such an extent that, for someone crossing the border, even an urban area like El Paso is now essentially as forbidding as the middle of nowhere.

Mount Cristo Rey

As a humanitarian aid volunteer along the US/Mexico Border who has seen countless atrocities enacted at the hands of CBP, witnessing the way Border Patrol engages with enforcement on Mt. Cristo Rey was unsurprising yet still horrific. It’s a very public and daunting display of Prevention Through Deterrence in action in the suburbs of El Paso. I think that oftentimes when we think of how Prevention Through Deterrence is enacted, we think of the border wall separating border towns, and of vast desert where people run and hide and walk for days journeying north. We seldom think of a suburb where the general public is in view of such atrocities, where 60+ migrants a day are being dusted by low-flying CBP helicopters.

We spoke to Border Patrol officers on the ground one day who said, verbatim, “It’s a game of cat and mouse, we are just trying to push them back into Mexico, there are too many of them to detain.”

Mount Cristo Rey is a site of Roman Catholic pilgrimage divided by the US/Mexico Border. The border wall ends at the base of each side of this rugged mountain, with a 29-foot-tall limestone statue of Jesus at its peak. From talking to people crossing through here, I gathered that many people wait for many days for a good moment to move down the mountain. Many of these people are not carrying enough water or food to sustain their wait, leading to injuries on the journey down, and possibly death. Many of the migrating people I have talked to on Mt. Cristo Rey were incredibly surprised to meet my crew, and surprised when I offered water and food and medicine. They remarked that people seldom, if ever, offer aid here.

This summer, the southwest desert reached record temperature highs, sustained for weeks on end. Countless people have died in every corner of the desert this year, and will continue to do so as long as Border Patrol continues inhumane tactics that perpetrate violence and death.

Ary (desert aid volunteer)

Mt. Cristo Rey, located in the El Paso suburb of Sunland Park, is one of the few remaining places in New Mexico where no border fence has yet been constructed (though Steve Bannon’s fraudulent wall construction did begin on the east side of the mountain.) This, along with the rugged terrain, has made this mountain a dangerous choke point for migrants crossing into the United States. Individuals and groups alike are vulnerable to an often-deadly game of cat-and-mouse with Border Patrol, and to other dangers in crossing, as described in the account above.

For ten years, there were a total of two deaths on Mt. Cristo Rey, but in 2023 alone, nine bodies were recovered on the mountain. There is no way to know how many of those who died farther north made their initial crossing on this mountain, but it is certain that BP’s enforcement strategies here makes the trip through Sunland Park more deadly.

El Paso

Thirty-foot steel border barriers, the Rio Grande, a network of canals, and a major interstate separate the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez from El Paso, TX. These barriers cause nearly all deaths in El Paso, with drownings, pedestrian motor vehicle accidents, or wall falls making up 83% of cases.

As in Sunland Park and Santa Teresa, many migrants begin their trip into El Paso by climbing the thirty-foot border barrier, resulting in numerous injuries and deaths, as discussed in other parts of this report [link to wall falls]. The Rio Grande and associated canals lay just past this border barrier, which at times makes classification of cases difficult. There are drowning deaths when the river is only a foot deep, suggesting that some drowning deaths are actually a result of falls from the border wall.

Water-related deaths make up over half of the 161 fatalities we have tracked within the El Paso city limits. Almost all of these deaths are due to the city’s canal system and the Rio Grande, which accompanies the border wall like a moat. El Paso Times reports that when upstream dams release water into the canals for irrigation season, the amount of drowning deaths, almost entirely of migrants, rises dramatically, with our data showing 15 bodies recovered from the city’s waterways in just two weeks in 2022.

Investigator reports will often mention that Border Patrol attempted a rescue, or that they yelled at migrants not to jump in the canals. While migrants have no way of knowing how deadly the quickly flowing canals can be, the line between a pursuit and a rescue becomes very blurry in these situations, as migrants are almost certainly fleeing Border Patrol, regardless of the agents’ intentions.

Similar to canals, migrants also face the barrier of the Cesar E. Chavez Border Highway and I-10, both of which run along the border, and which have caused at least 27 deaths in El Paso since 2016.

Search and Rescue and Emergency Response

This 20-year old woman, Mrs. Amanda Isamar Quito Vazquez, died of extended heat exposure.

– 2020 Doña Ana County autopsy report

Ms. Quito Vazquez was identified by an identification paper issued by the Ecuadoran government for its citizens, which is similar to the social security number in the United States. Reportedly Ms. Quito Vazquez had crossed the US border illegally, when she got weak and passed out. According to the Homeland Security Agent (HSI), Agent Licon, Ms. Quito Vazquez texted the coordinates of her whereabouts to her relatives. An individual, possibly the decedent’s brother, informed the Ecuadoran Consulate in Houston, Texas of Ms. Quito Vazquez’s situation. In the meantime, Ms. Quito Vazquez’s parents contacted their local police. Subsequently, the Consular General contacted the US Border Patrol, which mounted a search in the area of the reported coordinates and located the body of Ms. Quito Vazquez in the desert in Dona Ana County. Allegedly, there was a six day delay from the time Ms. Quito Vazquez texted her position until the US Border Patrol agents located her body.

Because of the segregated nature of search and rescue in the borderlands, migrants calling 911 are often left with Border Patrol as their only emergency responders. BP is notoriously slow to respond, if they respond at all, and in practice are not accountable to any other agency. Their “rescue” data has been shown to both inflate the numbers of rescues and also to reflect no useful data about the effectiveness of their response. As illustrated by the above linked report, BP’s response to a 911 call, even with adequate location information and advocacy from family and the appropriate consulate, can take a week, if it happens at all.

When dispatchers receive a distress call, they make a judgment decision about whether the caller is a border crosser—that is to say, they profile the caller—then pass the call along to Border Patrol, who may or may not take any action.

Humanitarian aid volunteers in the summer of 2023 received a distress call from the family of a Colombian man close to a highway. Though the man was just half a mile from the Santa Teresa Border Patrol Station, OMI data shows that Border Patrol failed to conduct a search for days after they had received the initial distress call. Moreover, aid workers experienced first-hand how Border Patrol actively prevented other agencies and individuals from searching on their own.

A friend reached out and said he’d gotten a report of a man missing in the desert about an hour from Las Cruces. The man, Johan, had last contacted his family the day before (Sunday) and sent them an exact GPS location of where he was. The pinpoint was less than half a mile from the Santa Teresa Border Patrol station, but Border Patrol refused to go look. I was returning to Las Cruces from out of state, without access to a car, and it would be several hours until I could go look for him. At that point it would be almost 9pm Monday, which would be long after dark and long after Johan had stopped responding to his family.

My friend reached out to a ton of people. Firefighters. Police. Border Patrol. I texted him the number of the local Search and Rescue group, who apologetically said they could not go look. My understanding is that they depend on BP’s abundant resources and trained rescuers to help out when US citizens go missing while hiking, skiing, ATVing. If they got involved with a migrant, they explained, they felt that BP might withhold those resources and trained agents in the future, which would threaten the lives of all the people they’re trying to rescue. They were very upset and kept asking us, “Why doesn’t BP go look?”

While we pleaded with people to go out, Johan remained alone in the desert.

I found a friend to go with me the next morning, Tuesday, and we were on our way to Johan when a search and rescue volunteer called and told me I didn’t need to come. A few of their volunteers decided that it was worth it to go search, even if it jeopardized their relationship with BP. He told me what they found at the exact pinpoint less than a half mile from the BP station: fresh ATV tracks, trash from the equipment used to recover Johan’s body, vultures following the odor that lingered. It was clear that BP had gone and recovered Johan that morning. By the scene, the SAR volunteers guessed he had passed away more than a day prior. I was so angry at BP for not even bothering to tell us they went to recover him. So many of us were coordinating a search that didn’t need to happen, and it put the SAR volunteers who went to look for him at unnecessary risk. They didn’t even bother to update us. That’s how little they care.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised when months later we got the autopsy report back and read that Border Patrol had already learned Johan’s location, which I would like to reiterate was less than one half of one mile from their station, more than a day before we did. The consulate or another SAR group had told them about it on Sunday, as soon as they learned from the family. Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised to know they care so little about life that they only went to look for him Tuesday morning, after he was already dead, even though they knew exactly where he was on Sunday.

Surprised, no. But I am so sad and sick and angry about it.

-Bees, desert aid volunteer

Sunland Park Fire Department is notable for responding to all distress calls in their jurisdiction, while not receiving any money from the federal government for these rescues. Chief Medrano stated in an interview with KTSM that the fire department is not in the business of finding out the legal status of people to whom it renders potential life-saving assistance. And for their part, the department advocated passionately, though ineffectively, for Border Patrol to respond to the above case. The segregation of emergency response is not inevitable; it is a choice, and can be changed when there is the will for it.

In the above case, some emergency responders expressed surprise that the individual was in distress so close to a road. “Why doesn’t he just walk to the road?” one asked. One implication of this database, which records many deaths close to roads and population centers, is that dispatchers, emergency responders, and SAR teams must take seriously all distress calls, even those that come from locations close to a road and in urban areas. They must also take action when BP fails to do so, and follow up on cases to ensure that there has been an adequate response. BP has proven time and again that they cannot be trusted to respond to emergencies, and the consequences are too dire to wait indefinitely for the agency to change these entrenched practices.

Demands and Recommendations

Customs and Border Protection and the agency’s Office of Professional Responsibility have time and again proven themselves dishonest in their accounting of migrant deaths and of CBP-related deaths. In this report, we reveal one small piece of what is missing from their data. But data and transparency will never bring back the lives lost, or stop the ongoing crisis of death and disappearance that is a direct result of US border policy. The only way to prevent the death and suffering that have become so commonplace in the US-Mexico borderlands is to end the policy of Prevention Through Deterrence, abolish the US Border Patrol, and dismantle the border barriers that have divided so many communities. At a minimum, we demand the following:

- While CBP should make good on its obligation to the GAO to provide complete data on migrant deaths and take transparency seriously, their accounting will never be trustworthy. Entities independent of border enforcement agencies must provide oversight, data collection, and accountability, working with state and county medical examiners, justices of the peace, law enforcement, and other organizations to make their data reflect the best information available.

- CBP and the OPR must apply CBP-related death designations consistently and transparently, and allow outside oversight of this process.

- Restrictions on asylum, like Texas Senate Bill 4, or those proposed by the White House and US senators for 2024, will cause death, injury, and suffering on the US-Mexico border, as people escaping violence, poverty, and climate change are forced to find alternative ways to enter the United States. In accordance with US and international law, CBP must open ports of entry to asylum seekers and remove all restrictions on access to the asylum process, including illegal policies of turnbacks and metering.

- End the practices of vehicle and foot chases which have made CBP the deadliest federal law enforcement agency in the nation.

- The border wall is a humanitarian disaster. Our data show the number of deaths caused by the wall are far higher than CBP reports. Walls have not reduced migration, but serve only to cause untold suffering; they must all be taken down.

Sources included in report

Protocol Development for the Standardization of Identification and Examination of UBC Bodies Along the U.S.-Mexico Border: A Best Practices Manual Binational Migration Institute University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (2014)

https://bmi.arizona.edu/sites/bmi.arizona.edu/files/protocol.pdf

“Symposium on Border Crossing Deaths: Introduction” by Bruce Anderson and Bruce Parks (2008).

Immigrants in New Mexico, American Immigration Council (2020)

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-new-mexico

CBP-Related Deaths, Office of Professional Responsibility (2021)

https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2023-Feb/2021-opr-cbp-related-deaths-report.pdf

The Disappeared Report Part IV: Left to Die, No More Deaths Abuse Documentation (2023)

http://www.thedisappearedreport.org/uploads/8/3/5/1/83515082/left_to_die_-_english.pdf

The Disappeared Report, No More Deaths Abuse Documentation (2023)

http://www.thedisappearedreport.org/

‘Mass disaster’ grows at the U.S.-Mexico border, but Washington doesn’t seem to care, AZCentral (2017)

https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/border-issues/2017/12/14/investigation-border-patrol-undercounts-deaths-border-crossing-migrants/933689001/

Border Patrol failed to count hundreds of migrant deaths on US soil, CNN Investigates (2018)

https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/14/us/border-patrol-migrant-death-count-invs/index.html

THE BORDER PATROL IS SYSTEMICALLY FAILING TO COUNT MIGRANT DEATHS, The Intercept (2022)

https://theintercept.com/2022/05/09/border-patrol-migrant-deaths-gao/

MIGRANT DEATHS IN SOUTHERN ARIZONA: RECOVERED UNDOCUMENTED BORDER CROSSER REMAINS INVESTIGATED BY THE PIMA COUNTY OFFICE OF THE MEDICAL EXAMINER, 1990 – 2020, Binational Migration Institute (2021)

https://bmi.arizona.edu/sites/bmi.arizona.edu/files/BMI-Migrant-Deaths-in-Southern-Arizona-2021-English.pdf

CBP Should Improve Data Collection, Reporting, and Evaluation for the Missing Migrant Program, United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees (2022)

https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105053.pdf

Department of Homeland Security U.S. Customs and Border Protection Notification and Review Procedures for Certain Deaths and Deaths in Custody, CBP (2021)

https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2021-Sep/2021_notification-review-procedures-for-certain-deaths-and-deaths-in-custody%20%283%29.pdf

CBP Deaths FOIA, R. Andrew Free

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/13KN2D5FIjIKJdgqFf5QrbiMkXssmJlm0SCsKev_gxSg/edit#gid=1978128881

Federal Deaths in Custody and During Arrest, 2021 – Statistical Tables, Bureau of Justice Statistics (2023)

https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/federal-deaths-custody-and-during-arrest-2021-statistical-tables

Mapping the Border Wall in Arizona and New Mexico, Wildlands Network, (2021)

https://wildlandsnetwork.org/resources/mapping-the-border-wall-in-arizona-and-new-mexico

A Taller Border Wall Brings a Surge of Costly Injuries to El Paso, Aaron Nelsen, Texas Monthly (2023)

https://www.texasmonthly.com/news-politics/taller-border-wall-falls-injuries/

Una joven hondureña muere al caer del muro de El Paso al intentar entrar en Estados Unidos, Marca (2022)

https://us.marca.com/actualidad/2022/04/17/625c2ef446163f62698b4579.html

Opinion: As a San Diego neurosurgeon, I see the devastating toll of the raised border wall, Alexander Tenorio, LATimes (2023)

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-04-13/draft-tenorio-on-border-wall-injuries

Migrants say they were seriously hurt in fall from border wall, then expelled to Mexico without medical treatment, Angela Kocherga, El Paso Matters (2021)

https://elpasomatters.org/2021/02/14/migrants-say-they-were-seriously-hurt-in-fall-from-border-wall-then-expelled-to-mexico-without-medical-treatment/

Emergency Driving Including Vehicular Pursuits by U.S. Customs and Border Protection Personnel, DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION DIRECTIVE (2021)

https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2021-Nov/CBP-directive-emergency-driving-Including-vehicular-pursuits-us-cbp-personnel-redacted.pdf

Chasing Danger: How Border Patrol Chases Have Spun out of Control, LATimes (2019)

https://www.latimes.com/projects/la-me-ln-border-patrol-immigrant-chases-crashes/

‘Hurting people’: The ‘cover-up teams’ operating on the US border, Mark Scialla, Al Jazeera, (2022)

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/12/12/the-cover-up-teams-operating-on-the-us-border

Metering and Asylum Turnbacks, American Immigration Council (2021)

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/metering-and-asylum-turnbacks

Five Things to Know About the Right to Seek Asylum (2022)

https://www.aclu.org/news/immigrants-rights/five-things-to-know-about-the-right-to-seek-asylum

EXPLAINER: Will immigration surge as asylum rule ends?, Rebecca Santana, APNews, 2022

https://apnews.com/article/public-health-immigration-asylum-54c11e091d464fe8d9272d607f6778f8

“We Can’t Help You Here” US Returns of Asylum Seekers to Mexico, Human Rights Watch, (2019)

https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/07/02/we-cant-help-you-here/us-returns-asylum-seekers-mexico

Judge denies bid to prohibit U.S. border officials from turning back asylum-seekers at land crossings, Associated Press (2023)

https://spectrumlocalnews.com/tx/south-texas-el-paso/news/2023/10/14/asylum-seekers-at-land-crossings

Court Allows Turnbacks of Asylum Seekers Without CBP One Appointments to Continue, American Immigration Council (2023)

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/news/court-allows-turnbacks-asylum-seekers-without-cbp-one-appointments-continue

U.S. Government Announces Sweeping New Actions to Manage Regional Migration, US Embassy in Chile (2023)

https://cl.usembassy.gov/u-s-government-announces-sweeping-new-actions-to-manage-regional-migration/

Immigrants And Asylum Seekers Are Not Bargaining Chips: Congress Must Reject Permanent Legislative Changes That Would Eviscerate U.S. Asylum Protections, NIJC Staff, National Immigrant Justice Center (2023)

https://immigrantjustice.org/staff/blog/immigrants-and-asylum-seekers-are-not-bargaining-chips-congress-must-reject-permanent

The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, Jason De Leon, Michael Wells (2015)

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520282759/the-land-of-open-graves

Border Patrol Strategic Plan: 1994 and Beyond, National Strategy, US Border Patrol, hsdl.org (1994)

https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=721845

Animal Scavenging and Scattering and the Implications for Documenting the Deaths of Undocumented Border Crossers in the Sonoran Desert, Jess Beck, Ian Ostericher, Gregory Sollish, and Jason De Leon, Journal of Forensic Sciences, Vol. 60, No. S1 (2015)

https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/110576/jfo12597.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

El Paso Plan Deters Illegal Immigrants : Border: A federal study finds Operation Hold-the-Line effective. But researchers say it causes staffing and morale problems for agents, James Bornemeier, Los Angeles Times (1994)

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-07-27-mn-20325-story.html

Operation Hold The Line – How El Paso Spawned Today’s Failed Immigration Strategy, Martin Paredes, elpasonews.org (2022)

https://elpasonews.org/2022/02/09/operation-hold-the-line-how-el-paso-spawned-todays-failed-immigration-strategy/

Texas’ Governor Brags About His Border Initiative. The Data Doesn’t Back Him Up, Lomi Kriel and Perla Trevizo, ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, and Andrew Rodriguez Calderón and Keri Blakinger, The Marshall Project,

https://www.propublica.org/article/texas-governor-brags-about-his-border-initiative-the-data-doesnt-back-him-up

Texas strings concertina wire along New Mexico border to deter migrants, Uriel J. Garcia, (2023)

https://www.texastribune.org/2023/10/17/texas-border-new-mexico-concertina-wire-abbott/

The Cost of Immigration Enforcement and Border Security, American Immigration Council, (2021)

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/the-cost-of-immigration-enforcement-and-border-security

Extending ‘Zero Tolerance’ To People Who Help Migrants Along The Border, Lorne Matalon, NPR.org (2019)

https://www.npr.org/2019/05/28/725716169/extending-zero-tolerance-to-people-who-help-migrants-along-the-border

‘Outsourcing’ border enforcement: Biden’s migration policies rely on Mexico despite its grim record, Conor Finnegan, ABC News, (2023)

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/outsourcing-border-enforcement-bidens-migration-policies-rely-mexico/story?id=99167102

Slack, Jeremy. Deported to Death: How Drug Violence Is Changing Migration on the US–Mexico Border. 1st ed. University of California Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dvjp.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dvjp

Separate and Deadly, SEGREGATION OF 911 EMERGENCY SERVICES IN THE ARIZONA BORDERLANDS, No More Deaths (2023)

http://www.thedisappearedreport.org/uploads/8/3/5/1/83515082/separate_and_deadly_english.pdf

CBP Nationwide Encounters

https://www.cbp.gov/document/stats/nationwide-encounters

Chambers, S. N., Boyce, G., & Martínez, D. E. (2022). Climate impact or policy choice? The spatiotemporality of thermoregulation and border crosser mortality in southern Arizona. Geographical Journal.

https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/664199

Ex-Trump adviser Steve Bannon among 4 indicted in alleged We Build the Wall fraud scheme, Kevin Johnson, Kristine Phillips, David Jackson, El Paso Times (2020)

https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/news/2020/08/20/former-trump-adviser-steve-bannon-3-others-indicted-alleged-we-build-wall-fraud/5616481002/

Death toll, waters rise in El Paso border canals with 5 bodies found in 3 days, Daniel Borunda, Aaron Martinez, Aria Jones, El Paso Times (2019)

https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/news/local/el-paso/2019/06/10/death-toll-waters-rise-drownings-el-paso-border-canals/1412997001/

Border Rescues and Mortality Data, CBP

https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/border-rescues-and-mortality-data

Podcast: Death By Policy: Crisis in the Arizona Desert, Julieta Martinelli, Roxanne Scott, Maria Hinojosa, Futuro Investigates, (2022)

https://futuroinvestigates.org/investigative-stories/death-by-policy-crisis-in-the-arizona-desert/podcast/

Three days stranded: How Border Patrol failed to rescue a lost migrant in the desert, Julieta Martinelli, Roxanne Scott, Futuro Investigates (2023)

https://futuroinvestigates.org/investigative-stories/death-by-policy-crisis-in-the-arizona-desert/an-update-to-death-by-policy/

Sunland Park Fire Chief ‘assuming’ passage of SB-4 will result in more migrant encounters, Leloba Seitshiro, KVIA (2023)

https://kvia.com/news/border/2023/11/16/sunland-park-fire-chief-assuming-passage-of-sb-4-will-result-in-more-migrant-encounters/

Migrant deaths mounting in desert west of El Paso, Julian Resendiz, KTSM

https://www.ktsm.com/news/migrant-deaths-mounting-in-desert-west-of-el-paso/